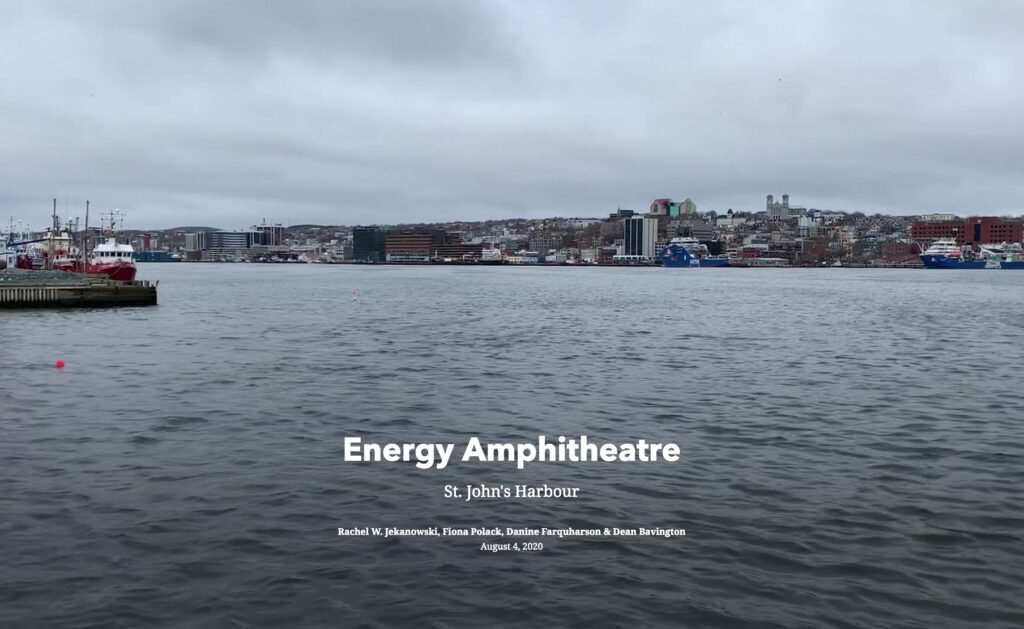

Energy Amphitheatre: St. John’s Harbour

This post by Rachel Webb Jekanowski, Fiona Polack, and Danine Farquharson first appeared on NiCHE, Network in Canadian History & Environment.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic we embarked on a project to discern how energy has shaped the harbour of Newfoundland and Labrador’s capital city, St. John’s. The context for our inquiry was participating in the Energy In/Out of Place Virtual Energy Humanities Research Creation Workshop, hosted by Anne Pasek, Emily Roehl, and Caleb Wellum at the University of Alberta in June 2020. Our team consisted of four non-Indigenous scholars who have lived in St. John’s, and worked at Memorial University, for varying lengths of time. While we share interests in place-based environmental and energy humanities research, our respective disciplinary backgrounds are in film, literary and cultural studies, and geography.

The Energy In/Out of Place organizers asked us, alongside research teams in California, Karnataka, Nunavut, and Quebec, to explore energy’s diverse roles in shaping our chosen localities, and to share our findings digitally with other workshop participants. We took a wide-ranging approach to both tasks.

Inspired by Cara New Daggett’s The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics, and the Politics of Work (2019) we considered the roles St. John’s Harbour has played in the ongoing resource extraction of oil, fish and seals, but also less readily obvious, less instrumental, flows of energy associated with creative labour and communication histories. Thus, we focussed on the Harbour as an energy amphitheatre: a place where diverse energy encounters and expenditures are uniquely amplified and visible. Conscious of the limitations of our non-Indigeneity, we were acutely aware that St. John’s Harbour has long been ground zero for the project of colonizing Newfoundland and Labrador, with disastrous consequences for Beothuk, Mi’kmaq, Innu, and Inuit peoples.

Mapping the Harbour

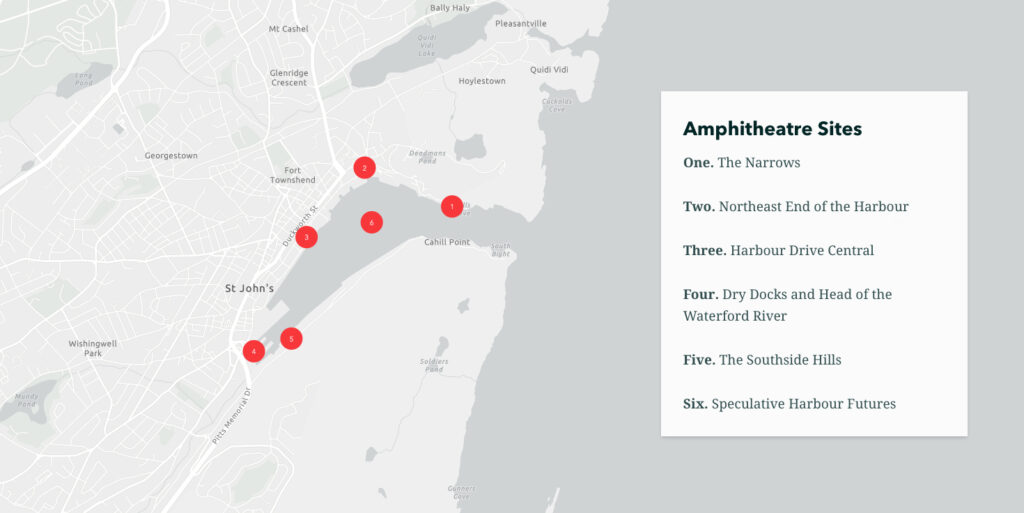

In keeping with the complexities of the energy flows animating St. John’s Harbour, we produced a digital humanities research-creation project in the form of an ArcGIS StoryMap. Like Katie Hemsworth, we wanted to bring a “multi-sensory experience” to our storytelling.1 We thus engaged practices of mapping through a sedimentary, affective model that layers historical traces (archival photographs, films, sound recordings), contemporary sounds and images we recorded on site, remediated archival materials, and affective and creative writing experiments onto a “base map” of St. John’s Harbour (Fig. 1). The resulting StoryMap comprises different histories, presents, and speculative futures, intersecting and sometimes resting uncomfortably alongside each other. The layering practice also enabled us to better explore the idea of collaborative, place-based affect, while playing with the positions of separate voices within the project’s whole.

The geomorphology of the Harbour varies as one moves around it. We thus had to consider the basin from multiple perspectives. Using writing prompts heavily influenced by suggestions from the Energy In/Out of Place organizers, we decided to conduct “affect experiments” in different parts of the Harbour. This decision immediately raised a question: how do we write affect collaboratively? Given the pandemic, each of us would be sharing our individual experiences and creative responses to the Harbour; yet, we were committed to developing a collaborative media piece.2

In the end, our process had three main stages: we picked a specific day (15 May 2020) during which each of us went to a different site around the Harbour to contemplate our prompts; we made notes and sketches on paper, took photographs and video, and recorded audio. Secondly, we wrote responses to artworks about the Harbour. Thirdly, we generated material to fill gaps in our circumnavigation of the Harbour basin and integrate stories of Indigenous interactions with the Harbour and its waters (Fig. 2). While the StoryMap software did allow us to layer material, its linear structure sometimes constrained our creative impulses and approaches to storytelling.

Collisions of Energy Theory and Practice

Energy histories have a funny way of infiltrating the present. One unanticipated aspect of our collaboration was that it spilled over into activist work around the centrality of oil within Newfoundland and Labrador. The COVID-19 pandemic hit the province’s offshore oil industry particularly hard, with visible (and sonic) effects on the Harbour. With the strong support of the provincial government, the oil sector began lobbying aggressively for a federal bail-out. Last May, Memorial University’s President Vianne Timmons intervened in the situation by participating in a pro-oil virtual news conference. She stated that “the oil and gas industry and Memorial University are intrinsically linked” and share a common goal of ensuring a strong offshore oil industry.3 Our collaboration on Energy Amphitheatre became the basis for another project: drafting an open letter to the university’s senior administration objecting to the yoking of NL’s public education to the future of extractive industry.4 This campaign presented an additional opportunity to think through the many tangible ways that petroculture frames public education, governance, and economic discourse in St. John’s and Canada.

While the environmental humanities has long focused on the ways that literature, film, and the arts represent human and nonhuman worlds, environmental history has been slower to engage with arts-based methodologies. However, research creation is gaining attention as an interdisciplinary approach which combines theory, experimentation, and art practices.5 Our StoryMap integrates more established methods from cultural geography, such as place-based storytelling and GIS software, with arts-based practices like creative writing, sound-mixing, and painting. We experimented with ways of historicizing the Harbour’s energy flows while explicitly centring those practices of mediation by which we experienced these geographies. Creative, technological, and embodied practices are the very acts of place-making: the ways people shape the meanings of the worlds around them. In other words, archival interventions like submerging photographs into the Harbour’s waters (Fig. 2) are tools of the imagination, ways of time-traveling into the past. We extrapolated from these energy histories into speculative futures using sounds and ecotopian designs of possible Harbours.

Our Energy Amphitheatre project also raised interesting questions for us about what it means to research and write in place. Unlike some scholars involved in the Energy In/Out of Place workshop, we were able to walk, bike, and drive down to the Harbour throughout the early months of the pandemic. As the climate crisis continues to trouble academia’s reliance on carbon-intensive research travel to field sites, archives, and conferences, projects such as Energy Amphitheatre offer potential examples of alternative, lower-carbon ways of conducting historical research.6 As Sarah Pickman writes, historians need to question the field’s assumptions about the benefits of “going there”: of balancing the insights and sense of legitimacy that travel can give us with the very real financial, racial, gendered, and citizenship privileges that it requires.7

We invite you to explore our StoryMap in its entirety below. An artist book, Energy In/Out of Place, featuring reflections on the research-creation workshop, is forthcoming in early 2022 under the Petrocultures and Mystery Spot Books imprints.

Rachel Webb Jekanowski is an incoming Assistant Professor in the English Programme at Memorial University’s Grenfell Campus and a former Banting Fellow (2019-2021). Her research and teaching focuses on entanglements of environments, power, and visual culture. Twitter: @stalebreadzine

Fiona Polack is Associate Professor in the Department of English at Memorial University, and Academic Editor at Memorial University Press. She works in the fields of energy and environmental humanities, island studies, and settler colonial studies. She currently leads the SSHRC Insight project “Oil Rigs and Islands” (2020–25), and recently co-edited Cold Water Oil: Offshore Petroleum Cultures (Routledge: 2021) with Danine Farquharson.

Danine Farquharson is Associate Professor in the Department of English at Memorial University. Her early research focused on Irish literature and film, but has moved into energy humanities, specifically collaborating with Dr. Fiona Polack on Cold Water Oil. She is the co-founder with Dr. Julia Wright of Dalhousie University of SSHORE: Social Science and Humanities Ocean Research and Education.

1 Katie Hemsworth, “Resituating and Resounding Interdisciplinary Research on Past Environments through Historical GIS,” Network in Canadian History and Environment (March 4, 2021): https://niche-canada.org/2021/03/04/resituating-and-resounding-interdisciplinary-research-on-past-environments-through-historical-gis/.

2 Kathleen Stewart, Ordinary Affects (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

3 “Virtual News Conference in Support of NL Offshore Oil and Gas Industry,” 26 May 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sBJLRVmSaGI.

4 Rachel Jekanowski et al., “Open Letter to Dr. Vianne Timmons,” last updated 8 June 2020, https://sites.google.com/view/munopenletter/open-letter.

5 Natalie Loveless’ How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation (Duke University Press, 2019) offers an overview of the recent growth of research creation programs and approaches in Canada.

6 For perspectives on the growing “no fly” movement within academia, see Diana M. Valencia, “The Carbon Footprint of Environmental Research: A Personal Dilemma,” Environmental History Now (October 24, 2019): https://envhistnow.com/2019/10/24/the-carbon-footprint-of-environmental-research-a-personal-dilemma/ and Hannah Knox, “A Year Without Flying” (July 2, 2019): https://hannahknox.wordpress.com/2019/07/02/a-year-without-flying/. Anne Pasek argues for the need to develop low-carbon research methods in “Low-Carbon Research: Building a Greener and More Inclusive Academy,” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, no. 6 (2020): 34-38. See, also, the white paper “Making and Meeting Online” (October 2020) emerging from the Energy In/Out of Place workshop written by Anne Pasek, Caleb Wellum, and Emily Roehl: https://www.energyhumanities.ca/news/making-and-meeting-online.

7 Sarah Pickman, ““Are There Even People There?” Re-reading Adrian Howkins and Grappling with “Going There”,” Network in Canadian History and Environment (August 10, 2021): https://niche-canada.org/2021/08/10/are-there-even-people-there-re-reading-adrian-howkins-and-grappling-with-going-there/.