Sustainable Academia: Marianna Dudley on university strike action in the age of climate change (Part 2)

This post is part of a series on Sustainable Academia—in cooperation with the Next Generation Action Team (NEXTGATe) of the European Society for Environmental History—in which contributors reflect on the conditions of historians in Europe and beyond (especially those in early career stages), introduce visions for the field, and suggest concrete action in order to build more inclusive and supportive academic environments.

On a gloomy January afternoon, H4F members Sam Grinsell and Elizabeth Hameeteman spoke with Dr. Marianna Dudley, a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Humanities at the University of Bristol and Vice President of the ESEH, about the ongoing strike action at universities across the UK. She candidly shared her take on being on the picket line as a member of the University and College Union (UCU) and how such collective action can also inform calls to action in response to the wider climate crisis. This is the second half of our conversation, read Part I here.

* * *

Continuing where we left our conversation about how historical thought or practice might inform collective action within academia, Elizabeth follows up on how Dudley mentioned the relationship between employees and employers. She asks, “How does strike action and other activist activities also involve a different relationship between students and staff?”

“That’s a good question,” Dudley says. “I feel like I’m a strike veteran now because we’ve been on strike nearly every year since I started my job about six years ago.” Through her experiences, Dudley feels that there has been a tangible shift in student attitudes towards lecturers and other university staff on strike in those years. “I think that at the beginning there was a real resistance in the sense that we were taking the education away from students, but since then the narrative has really changed.” Continuing on, “I think that’s partly because the discourse surrounding the strike shifted, lecturers and others have been able to say that the reasons behind the strike relate to the conditions in which students have to learn within.” It is not for nothing that ‘our teaching conditions are your learning conditions’ is one of the most-seen strike slogans.

Indeed, “there’s a strong sense now that those two go hand in hand,” Dudley explains. “Students aren’t happy with the way they are being treated as, well, cash cows by universities who are making them pay extraordinarily high rent and fees, treating them like consumers.” Dudley feels that students do not want to be treated in that way, “they understand that university education is about so much more than that transaction.” Students recognize that there is “something much more meaningful that goes on at a university, and that the relationships with their professors are really important to them.” This year in particular, “we have received really strong support from students, joining us on pickets and speaking out against unfair treatment of staff by universities.” Indeed, students have voiced their concerns and want to see change as well, “because ultimately it’s going to benefit them too.” To Dudley, this has certainly been a positive outcome of the strike action, that the narrative of what constitutes an university has been turned back to that relationship between staff and student.

To build on this, Sam asks whether Dudley could say something about how the strikes also involve professional services staff.

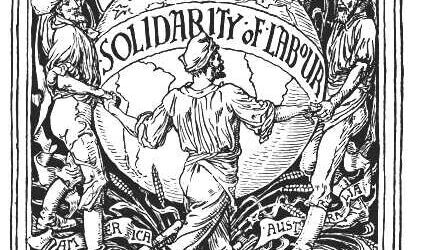

“Oh absolutely,” Dudley responds, “it’s really important to know that these strikes are not just about lecturers and professors, it’s about all university staff.” The fact is, “we can’t do our jobs without the support of professional services, they are crucial to academic life and they have also been squeezed in terms of their working conditions.” While pitted against each other at times, Dudley explains, “the strike has helped us see how changes affecting the one are also affecting the other.” The move towards causalization, for instance, “that’s hard on professional services when there’s no consistency and when new people are starting all the time who need guidance through complex university systems–those burdens fall on them.” As she puts it, “we rely on library staff, we rely on admin support, we rely on the porters who keep the buildings safe for us to work in.” Especially in these pandemic years, “we as academics rely on those other colleagues at the university to do our jobs and, therefore, we need to show solidarity with them–and strike is one way of doing that.”

Sam asks, “Does the type of activism that scholars in the UK are practicing shed any light or open up any possibilities for climate action?”

“Firstly, I would say that one thing that we have in the UK that I’m really proud of, and happy to be a part of, is a strong collective identity as academics, as university staff, and as union members.” Dudley explains that this might be something for places elsewhere to perhaps develop further, referencing the recent unionisation efforts of graduate and undergraduate workers at Columbia University. “It shows that that kind of collective action works, unionisation works–and I think we need to see more of it in academia.”

“You certainly have to take the hits along with the successes,” Dudley maintains, “but in the broader scheme of things collective action does work.” As she says, “being in a union helps manage some of the difficult and sometimes painful hits and also gives a kind of necessary hope that things will change for the better–and perhaps that’s something that can apply to climate action too.”

When thinking about the climate crisis, a sense of feeling can certainly exist about the issues at hand being beyond our control. “I don’t think that through this strike action we’re going to change the neolberal system in which we live and work, but I do think that we can save ourselves from its most pernicious effects.” With that in mind, Dudley hopes that collective action on climate can also offer some hope. “We need radical system change and we need new modes of thought and governance and so on,” she asserts. “Maybe strike action or civil disobedience won’t immediately get those things,” Dudley admits, “but I do think it breeds a sense of intent and hopefulness that action is better than none at all.”

When looking at activist groups like Extinction Rebellion (XR), for instance, “some people certainly don’t like their methods that are at times purposefully disruptive, but it does get the issues talked about and make people aware of the problem.” Dudley references the recent action by Insulate Britain to block traffic in the M25 ring road around London as an example of that. “People were really annoyed about not being able to get to work but actually, I think nearly everyone now understands what Insulate Britain means and what they stand for.” As Dudley explains, “when a green politician next talks about the needs for insulation alongside renewable energy subsidies or something, that work has been done through the collective action to connect those issues in people’s minds.”

While it’s a daunting task to address the complexity of the climate emergency for Dudley, it’s a simple one at the same time–as long as people take action. “Some days I’m really despondent about it all and others I’m much more hopeful,” Dudley admits. “But I think in general going on strike makes you much more positive that individual action can lead to collective change.” Perhaps “that alone would be a lesson for being part of a bigger group working towards climate action, whether it’s XR or any other group,” she says. “I think it can help stave off that feeling that we’re all alone and nothing’s ever going to change.”

“I really like what you said there,” responds Elizabeth. “It’s something that I certainly have felt too. But I remember something once said to me, that you might not be able to change the whole world, but you can change your world–meaning that you can inspire people to change through individual action.”

“And that there’s a sense of momentum that builds,” Dudley adds. “Sure, Jeff Bezos is frustratingly wasting billions by flying into space, but if beneath all that chatter actually a momentum is building among ordinary people, then I think that is what drives the political change ultimately–and that’s what we have to hang on to.”

“Perhaps it’s about that sense of hope,” Elizabeth says.

“Indeed,” Dudley responds, “and if we think about the idea of sustainable academia and so on, then we should take seriously that our jobs are worth doing and that our workplaces should be ones that look after us–and that does fit into hopes for a better planet to live within.” To be sure, “those are not kind of incommensurate things,” she says, “we’re not working for oil companies, we’re working for universities, and we’re trying to contribute to knowledge about what is going on environmentally in particular,” Dudley concludes.

“It’s worth doing that work and it’s worth making our workplaces support that work.”

1 Response