What does home look like now? The Marshes of Mesopotamia and sustainable academia

This post by Somayyeh Amiri is part of a series on Sustainable Academia—in cooperation with the Next Generation Action Team (NEXTGATe) of the European Society for Environmental History—in which contributors reflect on the conditions of historians in Europe and beyond (especially those in early career stages), introduce visions for the field, and suggest concrete action in order to build more inclusive and supportive academic environments.

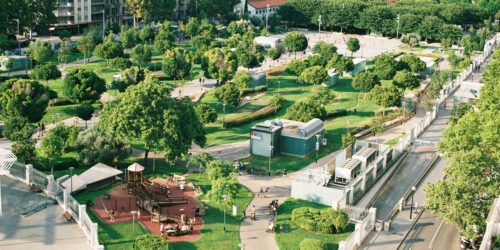

It might be easy to look at the water flowing underneath grasslands and reed houses and say, what beautiful homes! But look closer, where are these homes today? Much has been said about what a sustainable house should be, but what about sustaining the feeling of being at home? Is it anything other than that home is where you can find peace and security? For the people who live in the ancient Marshes of Mesopotamia, this feeling has been severely challenged and needs serious attention. This post asks how scholarship can help nurture and restore a place like this.

Academia can be a place where ideas, ecosystems, and people come together to cooperate. Thus, it can have an important role in amplifying the voices of ordinary people. A good example is Chris Riedy’s idea of “Discursive entrepreneurship: ethical meaning-making as a transformative practice for sustainable futures,” which opens up new possibilities for achieving sustainability. He describes how to build a meaning-oriented discourse-based transformational practice. On this basis, he introduces the concept of “discursive entrepreneurship” which is the process of creating, implementing, and transforming stories, narratives, and memes to shape a specific discursive perspective. Through this, he seeks planet-centric narratives to maintain the Earth’s heritage for the future (you can find more about Chris’s work here). Connecting such ideas to create a network and community can help create the sustainable landscape we seek.

I would like to point out a specific site that deserves our attention in considering how to build a sustainable future. This place was once the focus of many collective demands to be heard and seen, not in academia, but in the media to legitimize war in the Western public imagination. Now is the time for academia to see and hear more.

The Garden of Eden

The wetlands in southern Iraq and southwest Iran are known as the Iraqi Marshes. They were once the largest wetlands ecosystem in Western Eurasia. Historically the area covered 20,000 square kilometers, mainly comprising the Central, Hawizeh, and Hammar Marshes that are all separate but adjacent. The marshes support rich biodiversity and the Marsh Arabs’ unique culture that is firmly rooted in this watery landscape.

During the 1950s and 1970s, as part of agricultural development and oil exploration, the marshes were drained. However, Saddam Hussein accelerated the process between the 1980s and 1990s to drive out Shia Muslims from the marshes following the Shiite revolt against him. Before 2003, compared to their historical range, 90% of marshes had been drained. The marshes have partly recovered since the fall of Saddam Hussein, but have been negatively affected by drought, poor water policy, and dam construction upstream, including in Turkey, Syria, the Autonomous Kurdistan Region, and Iran.

The Marsh Arabs have a culture grounded in the marshes’ natural resources. For thousands of years, they have managed natural resources and created a lifestyle that connects them uniquely to their wetland ecosystem. After forced displacements, most Marsh communities lived in areas adjacent to drained marshes and abandoned their traditional lifestyle to adapt to conventional agriculture, in towns or refugee camps in other areas of Iraq, or Iranian refugee camps. But, after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, many Marsh Arabs returned to the marshes. In addition to the joint efforts of the Iraqi government, the United Nations, and U.S. agencies, Turkey’s record precipitation also helped the marshes begin to recover. However, the marshes have been reduced by drought and upstream dam construction and operation, and today, only exist as fragments of cultural heritage. According to activists, dams negatively affect local livelihoods and the environment. The Mesopotamian Marshlands became Iraq’s first national park in 2013, and since 2016 have been listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

As you might have guessed, despite all the efforts on the marshes and UNESCO warnings about the possibility of re-destruction of wetlands, history repeats itself here. This time, it is crucial for academia to focus on environmental policies at the local, regional, and national levels and also the connection and interaction of local people with their environment following forced displacements. When they returned after years of displacement and forced migration, a sense of insecurity in the settlement and political and cultural disconnection were ignored. The aftermath of this has led to the social and environmental crises that threaten the natural-cultural heritage of the marshes. Therefore, preserving the Iraqi Marshes must be done in harmony with its residents’ revitalization. Academia has an urgent role to play in realizing this and developing sustainable approaches for managing natural resources that are compatible with the traditions of the Marsh Arabs.

For academia to provide a platform for living sustainably, it has to, first and foremost, narrate the past lives of the Earth and the creatures that inhabit it, and on the other hand, hear and listen to the Earth and its people, past and present. This process can help recover relations between people and the planet. So, academia must take responsibility for the habitats that our past has left behind, and encourage its inhabitants to find their way to a sustainable future. It is a great opportunity to collaborate in making a suitable future by opening up chances for new concepts and the multiple meanings that narratives and voices bring. These narratives can create a community of people who grow the future from the roots of their natural and cultural past. Therefore, the role of academia is vital since it can provide a context for human experiences of life, in particular, indigenous and small communities that may be at risk of losing their connection to their past due industrialization, colonialism and ongoing exploitation. And this is where academia can maintain a connection to the stable future by raising voices that the powerful seek to silence.

Somayyeh Amiri is a Materials Engineering graduate, working at the intersection of materials, natural resources, humans, and the environment, with a special interest in historical perspectives. She is currently conducting research on how the concept of home and caring for it, in bio-cultural territories, is affected by environmental changes. Here are more details about her education and experience.